The ability to cope successfully with conflict is among the most important social skills one can acquire. The COVID – 19 era has highlighted a number of challenges that have been part of our society but, never as evident as they are today.

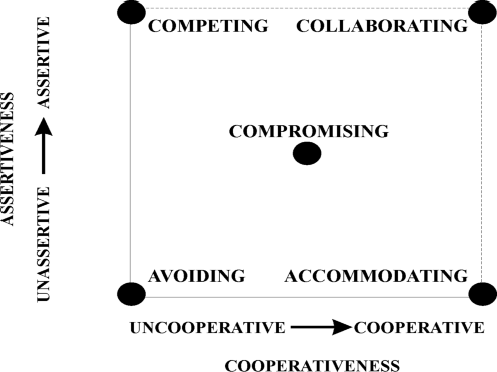

One of those challenges is mental health and with mental health comes conflict; conflict at home, in the workplace and intrapersonal conflict. I’d like to take this opportunity to speak about conflict in a more socially acceptable way. A model developed in 1976 by Kenneth Thomas and Ralph Kilmann, provides an excellent framework for learning various conflict‑management behaviours, their situation‑specific assets and liabilities and the consequences of using a particular style too much or too little. A scientifically proven model that has been validated and reliable, it has been used the world over by conflict resolution practitioners, mediators, management consultants and a number of courses that are offered by colleges and universities. I know it is the model that I have utilized and applied since 1980 with great success. The model describes the behaviours of each party in a conflict situation along two behavioural dimensions: one is assertiveness, defined as being the extent to which the individual attempts to satisfy his/her own concerns, and the second cooperativeness, the extent to which the individual attempts to satisfy the other person’s concerns. These two dimensions define five distinct styles for coping with conflict: competition, collaboration, avoidance, accommodation, and compromise.

Competition:

Competition (often referred to as a “SHARK” position) reflects a desire to meet one’s own needs and concerns at the expense of the other party. As the conflict model in this article illustrates, the most assertive and least cooperative people use the competitive style. To achieve the desired outcome, the competitor uses whatever power is available and acceptable, i.e., position or rank, information, expertise, persuasive ability, economic sanction, or coercion.

If the stakes are high enough, a very competitive person’s use of power may well be limited only by some greater external power such as the law or social taboos. Some advocate the use of the competitive style in all actual or potential conflict situations, which is not surprising given the endless models and reward systems that foster and support competition in our society. Competing (or any other style) is neither good nor bad, but one of many styles that may be appropriate and effective, depending on the situation.

Life‑threatening situations requiring quick, decisive action may require a power‑oriented competitive style. A competitive style may also be necessary at times to protect oneself from others who tend to take advantage of non competitive behaviour. In business, this style may be a must in those situations that require quick and decisive action at an operational, tactical or strategic level.

Someone who uses a competitive style to the exclusion of the other styles, may find that other people object to being forced into win/lose situations. Competitors do not yield their positions and often express anger and frustration openly and aggressively toward those who disagree. Other people learn that confronting a competitor brings negative consequences, so consistent competitors may not receive important information and feedback from others. Consistent competitors may be seen as belligerent and they may ultimately be cut off from interaction with others.

People who never use the competitive style may also suffer adverse consequences. They may feel powerless against competitors especially. In addition, the individual may be ineffective from lack of practice if he or she elects to use the style.

Collaboration:

Collaboration (often referred to as the “OWL” position) involves the maximum use of both cooperation and assertion. Those using a collaborative style aim to satisfy the needs and concerns of both parties. Collaborating means (1) acknowledging that there is a conflict; (2) identifying and acknowledging each other’s needs, concerns, and goals; (3) identifying alternative resolutions and their consequences for each person; (4) selecting the alternative that meets the needs and concerns and accomplishes the goals of each party; and (5) implementing the alternative selected and evaluating the results.

Collaborating requires more commitment than the other styles and takes more time and energy. It follows that such commitment must be warranted by situations in which the needs and concerns of the parties are extremely important and cannot be ignored. Going through the collaboration process can also lead to personal growth as the parties involved explore and test their values, assumptions, and potential solutions.

Collaboration requires a substantially greater commitment than do the other conflict‑management styles. Many issues simply do not warrant the time and energy required to seek optimal solutions, and not all conflicts are worth resolving or even lend themselves to resolution. Collaboration is being overemployed if seeking resolution to conflict is tapping energy needed for other activities.

One‑sided commitment to collaboration can also result in advantage being taken of the person who attempts to reach a mutually satisfying resolution. Because collaboration requires openness and trust, if only one of the parties to the conflict is willing to be open and trusting, that party will be at a disadvantage.

Creative ideas and solutions to complex problems are more likely to emerge through collaboration. For those who never use the collaborative style, they risk loss of innovative ideas, resolutions to the conflict and strong working relationships.

Avoidance:

Avoidance (often referred to as the “TURTLE” position) is characterized by both uncooperative and unassertive behaviour by both parties. Those employing this style simply do not address the conflict and are indifferent to each other’s needs and concerns. They evade the issue, withdraw from the discussion, or may not even stay for the resolution.

Avoidance can be employed effectively as either an interim or a permanent strategy. For example, if discussion is heated, it may be useful to allow the other person to cool down. At times, avoiding a situation until more information is available or an analysis of the problem has been made is the most productive approach. Temporarily avoiding a situation is also helpful if the issue is relatively unimportant, if there is not enough time available to come to a resolution, or if the issue is thought to be only a symptom of a more extensive problem that must be dealt with later.

As a permanent strategy, avoidance of the situation is indicated if the probability of satisfying one’s own needs and concerns is exceedingly low and there is no concern for the other party’s needs and concerns. Total avoidance is also called for if others can resolve the conflict more easily.

Many people assume that there are not adverse consequences associated with avoiding conflict. They assume that if they withdraw they have no responsibility and therefore there can be no negative consequences. On the contrary, too much avoidance of conflict can create problems for both parties. Participation in decision making fosters commitment to and subsequent implementation of the decision. If one person withdraws, decisions will be made and goals will be set with or without that person’s input, resulting in poor implementation of the decision and low levels of commitment to it.

The person who rarely avoids conflict may also encounter adverse consequences. Selectively avoiding conflict can be a good tactic to employ. Those who confront every conflict head on can hurt others’ feelings and stir up their hostilities. Selective avoidance is also the best way to keep from becoming overwhelmed by conflict, a distinct possibility in our society. The importance of every potential conflict needs to be weighed and a determination must be made about whether to avoid the situation.

Accommodation:

Accommodation (often referred to as the “TEDDY BEAR” position) is characterized by cooperative and unassertive behaviour. Accommodation means placing the other party’s needs and concerns above one’s own, even if one has very strong needs and concerns in the situation (which produces the conflict).

Accommodation is appropriate and effective if one party is not as concerned as the other. Accommodating the needs of the first party builds good will and leads to cooperative relationships. Accommodation is also effective when preserving harmony and avoiding disruption are especially important or when one person has a great deal more power than the other.

Those who use accommodation to excess may feel that their own ideas, needs, and concerns are not receiving the attention they deserve. Accommodators generally are “quiet” and are perceived that way to the extent that they are often not heard when they do make a contribution. Their influence, respect, and recognition may erode.

On the other hand, those who rarely use accommodation may be seen as unreasonable, and they may fail to maintain good relations with others because they do not acquire the good will that accommodation can bring.

Compromise:

Compromise (often referred to as the “FOX” position) is a midway between competition and collaboration and avoidance and accommodation. Moderate amounts of cooperativeness and assertiveness are required to affect a compromise. The person compromising expects that the outcome will be partial fulfillment of the needs, concerns, and goals of both people. Both search for a mutually acceptable, partially satisfying solution. Compromise results in more aggregate needs being met than would be met through competition and fewer met than would be met by collaboration. Through compromise more issues are confronted than would be confronted through avoidance, but issues are confronted less thoroughly than they would be through collaboration. Although the solution to a compromise is mutually acceptable, it only partially satisfies each person’s needs and wants. Therefore, competition is second to collaboration in degree of satisfaction produced.

Those who always compromise risk losing sight of what it would be like to have all their needs met. People who become caught up in the tactics and strategies of compromise and lose sight of important values and principles and the myriad possibilities.

On the other hand, people who never compromise may never develop the skills needed to bargain or negotiate when necessary. They may be unable to make concessions and may not be able to extricate themselves from potentially no‑win confrontations.

Summary:

Conflict is neither good or bad and some would say it is healthy. Depending on the environment and the parties involved, I wouldn’t necessarily agree with the healthy statement however, I do agree that it is part of our society that requires us to face it when the need arises. Whether a particular conflict‑management style is appropriate is specific to the situation and is the key element. To be effective at managing conflict, one must know that in a conflict situation – they have “FLEXIBILITY” and this is predicated to the five aforementioned conflict resolution styles. A person ought to be able to use any of the styles and know when each style is appropriate in order to be effective. However, people tend to develop one preferred style and use it in most situations and as a consequence may neglect styles that could be more effective.

Being able to make use of these styles implies leaving your ego at the door. When ego arises out of a conflict, emotions set in and nothing productive will happen when an emotional hijacking takes place.

Again, nothing is inherently right or wrong about any of the conflict‑management styles; each may be more or less appropriate and effective, depending on the situation and the parties involved.

Each of us has access to a variety of conflict‑management behaviours but we tend to prefer certain ones and to use them to the exclusion of other styles that could be more effective in a given situation – with adverse consequences. We ought to consider developing the necessary skills to execute any of the styles. When we can diagnose conflict situations and choose the appropriate method of dealing with whatever comes up, depending on our needs at the time and the importance of coming to a resolution within a prescribed time frame, then and only then can we play an integral role in resolving conflict.

About The Author.

Nicholas Pollice is President of The Pollice Management Consulting Group located in Southern, Ontario, Canada. An international presenter and consultant, he is known as a leader in operations management. Nicholas conducts programs in leadership, supervision, communication, negotiation and conflict resolution. He has been a consultant since 1989 and is the author of several professional publications. His presentations have been consistently ranked in the top10 % throughout North America. See Nicholas’ bio, his other publications and services on the PMCG. Website at www.pollicemanagement.com