Change, is traumatic and for some it can be good while for others – it can be frightening. Change by nature can challenge employment, make people feel somewhat threatened by any alteration in the status quo or give organizations a path forward to a more prosperous future.

Disruption accompanies change and these disruptions affect employees, leaders, resources, vendors and perhaps some clients. Organizations by their very being must change, and managers must implement changes and overcome resistance to them. This of course has never been more pronounced than the situation we find ourselves in today. From a positive perspective, COVID 19 has forced organizations to make changes that should have been made three to five years ago however, some of these changes are being conducted with little or no well thought out future goals or objectives in mind.

Dora Wang (Partner, Reed Smith Global Regulatory Enforcement Group, New York) says that most change efforts in organizations change because organizations are ineffective in choosing the right strategy for change. In her 2016 article titled; Change Management, she points out the following reasons for organizational change failure.

- 37 % of change efforts fail to meet targeted expectations,

- 23 % of change efforts fail because leadership behaviour does not support the change,

- 19 % of change efforts fail because employees are resistant and management fail to address this resistance,

- 12 % of change efforts fail because of a lack of adequate funding,

- 5 % of change efforts fail because of a lack of consistent and constant communication,

- 4 % of change efforts fail for other reasons.

Why Do Organizations Need a Change Strategy?

Developing and selecting the right change strategy provides direction and meaning for all change management activities. By identifying the unique elements of the change like risks, resistance, time lines, capital and resources; change implementers set themselves up for success. A “one size fits all” approach to change management strategies is not effective because all organizations are unique onto themselves. Just to name a few, wrap your head around these changes:

- acquiring a company of near or equal size,

- getting vendors to use a new web based payables system,

- implementing a COVID 19 alert system,

- relocation of offices,

- changes in corporate leadership,

- new vendor application,

- implementing a mental health policy and procedure.

All of these aforementioned changes have one thing in common – they are very different in nature and application and require a variable strategy for success. Change management strategies ultimately define the required approach given the circumstances and end goals of your change initiative.

Steps In Creating Strategies For Change.

- Identifying Change Characteristics:

Understanding and being able to define the change and its relative scope allows change makers the opportunity to formulate the base of successful change. Some elements to consider are:

- What is the change?

- What is the scope of the change?

- What does the change look like?

- How will the change be communicated?

- Where will the change happen?

- Who / what might the change affect (processes, systems, job roles, etc.)?

- When will the change take effect?

- Why is the change required?

- What is the timeline for the change and does it compete with other initiatives?

Nothing is so painful to the human mind as a great and sudden change

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, Novelist

- Taking An Environmental Scan:

Being knowledgeable in organizational change history culture is something to not be overlooked because it provides an insight into corporate culture and values. In essence, these two items (culture and values) are a strong indicator as to how an organization will accept and support the change. An environmental scan would include:

- What is the organizational back story that affects the change (eg: history & culture)?

- What is the perceived need associated with this change amongst employees, managers, corporate future?

- How have past changes been managed?

- What were the successes and failures of these changes?

- Is there a shared vision for these changes?

- Who are the employees affected by this change and what is the relevant impact of these changes? (revisit of step one)

- How does this change affect our corporate vision, mission and our strategic plan?

- How much change is taking place now in the organization and how does this change affect those current changes?

- Internal Audit:

Since we know that 23 % of change efforts fail because leadership behaviour does not support the change and19 % of change efforts fail because employees are resistant and management fail to address the resistance, an internal audit will enable us to anticipate some of the aforementioned behaviour while predicating success. At the internal audit stage consideration ought to be give to:

- Ensure that the leaders at the top of the organizational “food chain” understand the change and are on side.

- Seek feedback from all key change agents and listen to what they have to say.

- Redefine exactly what the change is.

- Create specific, measureable, achievable, realistic and time bound change parameters.

- Simplify the change into easily digestible pieces for mass communication.

- Expecting & Planning For Resistance:

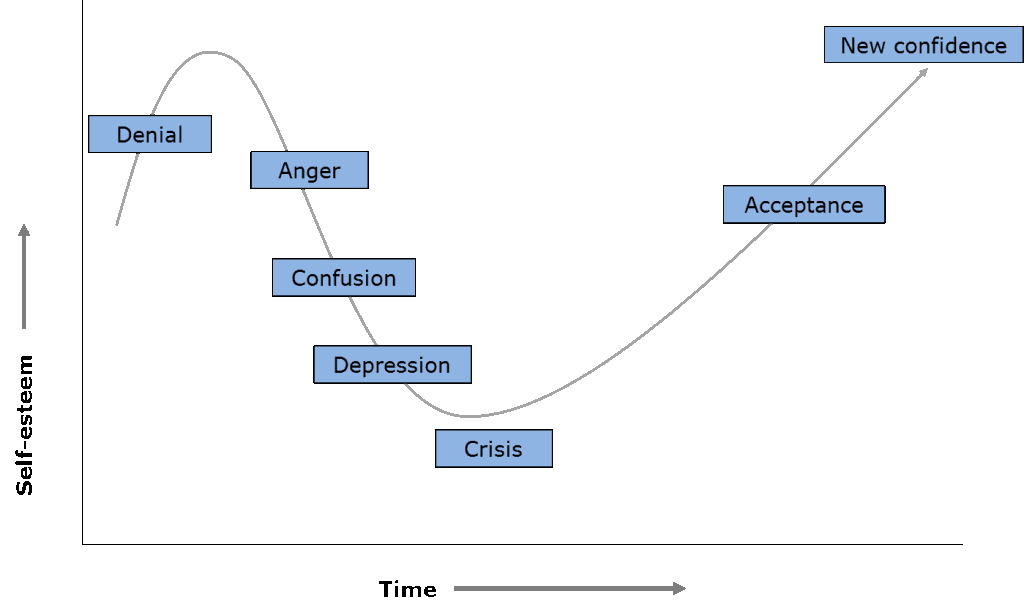

Expecting and planning for resistance to change is a prudent way of effectively anticipating and managing objections and allows you the opportunity to plan your change strategy. In his article “Change Rarely Comes Easily”, strategy consultant Torben Rick points to the following model (Figure One) of resistance that cloud peoples judgment and can make change difficult if not incorporated into a change management strategy.

This brings me to a law of physics. The original form of Newton’s Second Law states that the net force acting upon an object is equal to the rate at which its momentum changes with time. If the mass of the object is constant, this law implies that the acceleration of an object is directly proportional to the net force that is acting upon the object.

Therefore, Newton’s Second Law states that: Force (F) = Mass (M) X Acceleration (A).

So, what does this have to do with an organizational strategy for change? EVERYTHING! You see, if “Mass” is high, which implies that the scope of change is very broad and touches the most important aspects of our business the “Force” necessary to enable this change to take place, will be high.

Also, if “Acceleration” is high, which means change has to take place immediately or in a very short period of time, the “Force” necessary to enable this change to take place, will also be high.

Both these aforementioned scenarios have one thing is common; if force is high then “Resistance” amongst employees is high. The higher the “Resistance” the higher the “Force” resulting in dissension amongst employees.

Why, because change is based on a Bond of Trust. Change is about looking at opportunities, having vision, making sure that people understand the change; it is about establishing trust and producing short term positive results in order to move forward.

As managers we cannot always select the depth and breadth of change (Mass). That in most cases is an exogenous variable, it comes from corporate, however; in many cases we do have some control over the speed at which the change will take place (Acceleration). This is often referred to as an endogenous variable because it is derived internally.

So why are we going through all this, because the slower, more methodical and pragmatic change can be, the higher the probability of success and the less resistance will be encountered along the path of change.

Figure One

Summary:

Several events have confirmed the importance of organizational change. Today, more and more managers must deal with the pandemic, government regulations, new products and services, growth, increased competition, technological developments, and a rapidly changing workforce. In response, Kotter and Schlesinger argue (and rightfully so) that several organizations must undertake moderate organizational changes at least once a year and major changes every four or five years.

Few organizational change efforts tend to be complete failures and few tend to be entirely successful. Most efforts encounter problems; they often take longer than expected and desired, they sometimes run the risk of killing morale. Also, they tend to cost a great deal in terms of managerial time, emotional upheaval and capital resources. More than a few organizations have not even tried to initiate needed changes because the managers involved were afraid that they were simply incapable of successfully implementing them because of the absence of a well thought out strategy for change that has input from employees who are affected by the change and are expected to champion elements of the change.

About The Author.

Nicholas Pollice is President of The Pollice Management Consulting Group located in Niagara, Ontario, Canada. An international presenter and consultant, he is known as a leader in operations management. Nicholas conducts programs in leadership, supervision, communication, negotiation and conflict resolution. He has been a consultant since 1989 and is the author of several professional publications. His presentations have been consistently ranked in the top10 % throughout North America. See Nicholas’ bio, his other publications and services on the PMCG. Website at www.pollicemanagement.com